Pioneers of Environmental Black History

Pioneers of Environmental Black History:

This Black History Month celebrates the legacy of these pioneers, activists, educators, and inventors rooted in the Environmental Justice Movement that has helped shape anti-racist groundwork for Black communities, allies, and the planet.

Black America has a long standing history in the on-going fight for environmental justice. The intersections of race and the environment has become a leading conversation in pressing the need for systemic change in our climate actions.

Many have stepped up to demand and advocate for healthy, sustainable, liveable communities making sure that no person, despite race, ethnicity, social status, political power, or income, will be disportionately or negatively impacted by environmental laws and policies that are not protective of public health.

The response to environmental racism is environmental justice, and how we take our power back. These pioneers have motivated, inspired, and raised awareness that is widely sought after and admired today.

George Washington Carver (1865 - 1943)

"He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world."

George W. Carver was revered as the most prominent agricultural scientist, inventor, and educator of his time in the early 20th century. His research and diverse crop alternatives to cotton created solutions that restored depleted soils, advanced conservation, and improved farming methods. Although Carver was born into slavery, his naturalist artistic abilities and perserverance in education, being the first Black American to earn a bachelor and masters degree in science, ultimately led him world-renowned recognition throughout his life. He eagerly approached his work through a holistic lens that sprinkled science with faith, believing the two were interconnected like humans and nature. Up until his death, Carver’s legacy was set on helping others in which he succeeded in helping hundreds pioneer ecological and sustainable technologies.

MaVynee Betsch (1935 - 2005)

"This is the Beach Lady. If you’re getting this message, it may be because I have turned into a butterfly and floated out over the sand dune."

MaVynee Betsch was an environmentalist and activist famously known as The Beach Lady. Born into an upper class wealthy family in the South, her great-grandfather was the first Black millionaire, founder of the first insurance company, and oldest African American Beach in the state of Florida. She gained education from Oberlin Conservatory of Music, and moved to Europe to sing opera. In 1975, she relocated back to her great-grandfather's beach house, becoming fully invested in protecting American Beach from development or destruction. This was at a time when Black life was dominated by the structures of Jim Crow. Her efforts of public education and environmental significance worked towards preserving the sand dune and its local inhabitants. She generously gave away her entire life’s savings to over sixty environmental causes, and continued to benefit others even after being diagnosed with cancer. Up until her death, The Beach Lady was often seen with locks up to seven feet long and wearing colorful, whimsical dresses, lounging on her beloved beach. The American Beach Museum continues to hold all the history she embedded into her community.

Hazel M. Johnson (1935 - 2011)

“It takes such vigilance and activism to keep legislators on their toes and government accountable to the people on environmental issues.”

Hazel Johnson, or admiringly known as the ‘mother of environmental justice’ was an community environmental activist in the South of Chicago on a mission to bring clean air and water to her community. She resided in The Altgeld Gardens homes, connected to both a peaceful and serene setting while harboring a dark past buried beneath the soil. The land had once been a dumping site for toxic sludge, making the grounds heavily polluted, and the community extremely ill. After losing her husband to cancer, with an outstanding number of cases in the area, she began investigating the correlation between land and health. The housing unit had once been surrounded by 5o landfills and over 300 polluting sources, which had heavily tainted the communities water supply with asbestos, renaming the area “The Toxic Doughnut”. The immediate response was the formation of People for Community Recovery that Johnson founded in 1979. This work continued to fuel accountability on Chicago Housing Authority and prompt investigations on environmental racism. In 1992 Johnson received the President's Environment and Conservation Challenge award in recognition of her environmental work. Up until her death, Johnson was community focused and her legacy continues to live on supporting those in need of land justice.

Marjorie Richard (1941 - )

“The environment is everything around us — the air, the water, and the land. The Earth is the foundation of life. Environmental issues should never be ignored.”

Marjorie Richard stands between the intersections of race and the environment. She grew up in a predominantly Black community in the Old Diamond neighborhood of Norco, Louisiana. As a young girl, the four block radius of green fields and flowers she remembers had slowly become sandwiched between an oil refinery and a Shell plant. This would later give rise to the town nickname of “Cancer Alley”. Her activism began in 1973 after a Shell pipeline exploded killing two people, however, it was the refinery explosion of ‘88 that killed seven and pumped millions of toxins into the air that led her to found the ‘Concerned Citizens of Norco’ demanding Shell provide resettlement costs for the community. After 13 years of protest, Richard saw justice, as Shell reduced emissions by 30% and provided $5 million in resettlement costs to relocate the Old Diamond neighborhood. Her work continues to inspire health initiatives and advisors fighting for justice. In 2004, Marjorie received the Goldman Environmental Prize award in her dedication to successfully challenge environmental racism.

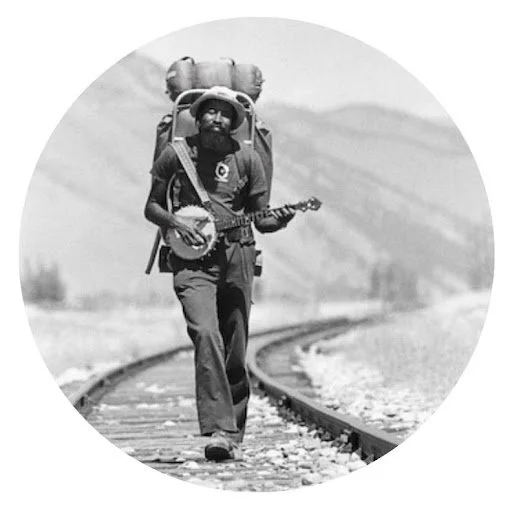

John Francis (1946 - )

“We are the environment and how we treat each other is really how we treat the environment”

Having taken one of the most unique strides in environmental activism, John Francis is known by all as the Planet Walker. After witnessing the oil spill of 1971 in the San Francisco Bay, Francis declared to no longer use motorized transportation having been deeply impacted by the effects of such destruction. For the next 22 years he walked everywhere across the lower 48 to highlight society's dependence on oil, and his travels even brought him down into South America. Francis found himself in frequent disagreements for his decisions which led him to take a day of silence to practice listening to others rather than arguing over differing perspectives. He spent the next 17 years in a vow of silence, playing the banjo, writing, and even completed a bachelors, masters, and doctoral degree in Land Management. On Earth Day In 1990, Francis ended his streak of silence, and was struck by a car the very next day, in which he convinced medics to let him walk to the hospital as he was still against transportation. In 1991, he was named the United Nations Goodwill Ambassador, and also is the author of Planet Walker: 22 Years of Walking, 17 years of Silence. The Planet Walker non-profit continues to provide communities with environmental education.

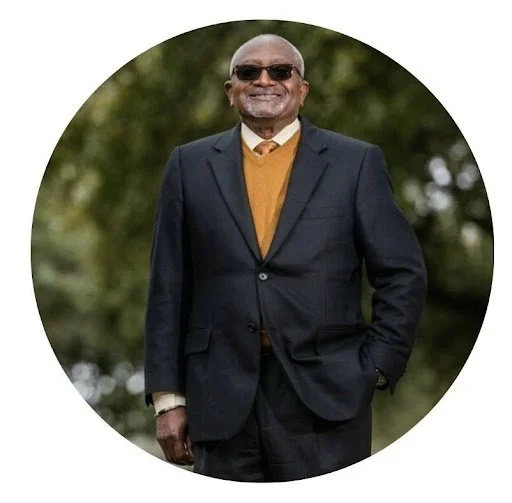

Robert D. Bullard (1946 - )

“Environmental justice is nothing more than this whole principle: people have the right to a clean, healthy, sustainable environment without regard to race, color, national origin. It’s just that simple.

Robert Bullard holds the honorary title as the ‘father of environmental justice’ since his academic activism rising from the 1980’s. For more than 40 years Bullard has expressed the detrimental impacts of pollution, land use and housing discrimination based on race and class. His research brought attention to minority communities being disportionately less likely to have parks, nature trails, farmers markets, and health stores in their neighborhoods, and more likely, situated in close proximity to toxic waste sites, incinerators, landfills, or highways. Bullard made advances on this awareness in Houston during a lawsuit filed by his wife to target the discrimination of a landfill going into a Black community. With the help of his students and gaining media coverage, research shows between 1930 - 1978 that 80% of solid waste was dumped into Black neighborhoods that only made up 25% of the population. With crippling health risks entering the community, he brought the topic of environmental racism to the whole South and saw alarming similarities. His work in bridging civil rights with environmental justice is now a staple in universities across the US, and readily accessible in the many written works he has contributed, including his first published book, Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality.

About the Author: Rosie Llewellyn is a Haitian - American artist, author, yoga teacher, and sustainability leader inspired by the beauty + abundance of our natural world. Often immersed in the mountains, chasing sunlight, and calling it poetry, Rosie aims to bridge the elements of creativity, movement, and earth wisdom to advocate for a sustainable way of life in balance with our planet.